After a getting a job in craft beer, one of the first and most startling differences I noticed was the vocabulary used by brewers in the comfort and privacy of their own breweries. I don’t mean colourful swearing (well, actually, now you mention it…) but rather the kind of words a brewer might use to describe their beer as opposed to a marketeer, PR, and therefore, many writers and bloggers. A lot of the language used to describe beer is inadvertently determined by label copy, the brewery’s tasting notes, other bloggers’ reviews, or even just the name of the beer itself. Put simply, there a some words brewers use casually that sales and marketing people would avoid entirely.

Recipe design, does not, as some might be surprised to learn, involve ticking off that never-ending list of tropical and citrus fruits that beer reviewers refer to so studiously. Increasingly, terms like ‘dank’ (resinous, earthy, cannabis-like) and ‘savoury’ (garlicky and oniony) are used not just liberally, but as positive terms. ‘This is great juice, but we should really shoot for a more oniony flavour next time’ are the kind of phrases I now hear and accept almost unconditionally. Brewers are often the first to use the language that eventually filters down to drinkers, way before it become part of the common parlance. ‘You’re going to love this new IPA guys, it’s our most oniony release yet!’ is not a tweet you’re likely to see very soon, but you can bet somebody in the brewery said it.

However, that sort of language describing these types of hoppy beers is now starting to gradually trickle through to consumers and budding aficionados, and this is because of the kind of beers being released. By way of example, a handful of articles and blogs have recently noted the rise of the ‘Yeast Coast’ IPA (included in a great post by Emma at Crema Brewery on what’s going on in IPA at the moment) in the States, a sort of cultural counterpoint to the pale, strong and bone dry West Coast IPAs. These beers that look like milk-thick fruit juice and smell like cannabis and hot dog onions are, to the astonishment of many, remarkably balanced, sharp and juicy on the palate with a pleasing savoury edge. They are complex, intricately-constructed and require a razor-sharp balance that is incredibly difficult to execute. They are impressive in so many ways but to describe them requires words with which not everyone is comfortable. How did we end up talking about beers like this?

For a long time, the buzzword in craft (and IPAs in particular) was bitterness. It was something that a layman could put their finger on and notice immediately as a point of difference between mainstream beer and craft beer. Hops had aroma and flavour sure, and a lot of the varieties being used were all about grapefruit and bitterness, so IBUs had a correlation of sorts with hop character. IBUs were the Top Trumps stat of choice, slapped onto label copy with a kind of swaggering braggadocio, as if it was the barbell weight the head brewer could deadlift anytime, anywhere, pal. It in turn influenced consumer habits. What’s the IBUs on that IPA? 150? *kisses biceps* No problem, dawg. I can handle it. We ended up with International Bro Units.

Of course, bitterness is relative, one of the tangible factors of flavour mitigated by the balance of others; a single number in a more complex equation. Imperial Stouts have huge bittering additions for balance, but don’t taste nearly as bitter as a lighter pale ale hammered to hell with Chinook. As a term, IBU has started to fall by the wayside. It’s a less useful way of understanding flavour than perhaps it used to be, if indeed it ever was.

Next, it was all about aroma and fruit. Ever more supercharged hop varieties were released, with brand names as finely honed as the latest miracle drug, sports car or running shoes. We wanted to know about fruits, and we weren’t just going to settle for grapefruit, oh no. Crap, I’ve never even had a gooseberry and mango sundae before but God damn it if it isn’t what this beer tastes exactly like, uh, I think. Increasingly myriad hop combos competed for the ultimate Carmen-Miranda-hat-fruit-salad of aroma and flavour. Whilst fruit and juiciness were what we were talking about, bitterness was still there, balancing out these super-fruity beers, keeping them dry and clean and drinkable. We just stopped talking about it. Savoury notes were there too, but so far beneath the radar of commenters that, in flavour description terms, they didn’t exist, like unseen falling trees. We didn’t see them because we weren’t looking for them.

And now? We’re starting to get into dank and savoury, pal, big time. Gimme some of that Mosaic and Summit-soaked onion-and-mango juice. It smells like a university dorm room and looks like a colour Dulux might call Terracotta Sunrise (Matt), but it’s taking my palate into new dimensions. I’m ready. I want to know more. I want to taste Other. Send me through the Stargate to the dank and savoury galaxy.

In many ways it’s a real victory. The tyranny of the word ‘lychee’ in beer blogging may at last be coming to an end. People are beginning to get comfortable with savoury and the dimensions of flavour beyond sweetness and bitterness. There’ll be reactions, appropriations, satire, over-exaggerations and all the usual resistance, but by the end we’ll all have richer vocabularies and more exciting beers. It’s just the next level we have to play through, and there will be plenty more beyond.

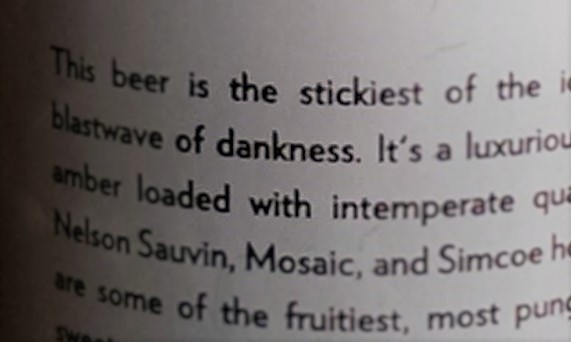

‘Danksauce’ was a phrase used by Modern Times recently, both casually on their website and social media, as well as on actual label copy (along with dank, dankness and more), which really struck a chord with the wordsmith in me. It’s kind of silly, but also quite heartfelt and honest about how weird beer can be sometimes and how not to take it too seriously. It sums up a kind of free-wheeling, ambitious yet laidback approach to tasting language and cavalier artistry in brewing that I wholeheartedly support.

Obviously, I’m a sucker for a snappy craft portmanteau. I fall head-over-heels for the hottest zymurgy wordplay. I love a Juicy Banger. I like anthropomorphising beers and flavours, and I think it’s because craft beer is, like language, constantly evolving. As a result, we’re not just getting better beer; we’re getting better at describing and understanding it.