Did we miss Craft’s chance to mature?

‘Grown-up’ is a descriptor strangely absent in a market of controlled substances for adult consumption. We read a lot about the craft sector’s vibrancy, enthusiasm, belligerence and sense of humour nowadays, but, by comparison, rarely about its maturity. However, as the old adage goes: the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. In fact, I feel like we did used to talk about it, then stopped.

Only recently, there was frequent talk of how quickly the craft sector of the UK’s brewing industry was ‘catching up’ with its equivalent in the United States. That distance, once measured in years, quickly became the length of a long-haul flight. It seemed to me, that what we were talking about at the time was the ‘maturity’ of the scene. Now, I feel that parity of esteem between UK and US craft might be true of certain innovations, brewing knowledge and technical capability, but ‘maturity’ is something else entirely.

In more human terms, if you just assume that you’re going to grow up at some point in your life, you probably won’t. Seizing maturity can happen in childhood or even later adulthood. There’s no fixed date. “The UK beer scene is starting to mature,” we might have thought (or heard, or read, or said), “because someone hasn’t released an alcoholic milkshake chocolate soda pop (today)”, or, more rarely, “because someone has done something very decent, and clever, within their grasp (today)”.

Of course, it’s difficult for us to define craft beer’s maturity in the same way it’s difficult to clarify the maturity of an entire city or nation of people of differing ages. However, based on the number of breweries that have started in the US and Europe in the past five years alone, we can say with some degree of confidence that the majority of breweries making craft beer are infants, or at best adolescent.

All of this was what was going through my mind when I read the tap list at Threes Brewing in Brooklyn, New York. It was long, but by no means unusually so. It featured beers in different serving sizes, styles and strengths – again, not that strange. What did stand out was that most of those styles weren’t IPAs. Those that were IPAs ran from West Coast to East Coast fairly evenly, while the lager and saison selection (typically, as those that know the brewery will agree) ran into double digits. Whilst nearly everything was American, this tap list, like the United Nations over the water on Manhattan, seemed to represent the world as its author wished it to be seen. It felt tangibly mature.

Back in London (or almost anywhere with an infestation of aluminium cans and pastel-coloured artwork), there is often very little fanfare given to anything but hazy IPAs in their technicolour tallboys. I believe that this has a lot to do with how we discuss and debate about beer, or rather, how we used to, versus how we do now.

Discussions and debates in blog comment threads and on Twitter have waned. Craft beer consumers scroll and double-tap now, and have changed both the social media landscape and production schedules as a result. There’s no time to type, or respond, or think. When it does happen, it’s often as privately as possible, and typically with the safe, reaffirming vacuum of a private group chat or forum. The craft beer consumer feeds on their own opinions in reflection, and debates, when they do happen, are feverish in their heat and lifespan, destroying themselves in the process.

This is all normal now, and it happened quickly. Very, very quickly. Hazy IPAs are not the only symptom of this current malaise, but their rise to prominence in UK Craft makes for a useful case study.

I have a sticker on one of my notepads, from my time at Brew By Numbers. It was made for the release of 21|03, the first East-Coast-inspired pale ale from BBNo. I designed and printed rolls of these stickers, to be affixed to every case and keg of the beer. On the sticker, and in an accompanying blog post (no longer available), we had explained (reassuringly but without apology) that this juicy pale ale’s turbid appearance was natural and nothing to be afraid of. The appearance and the flavour were co-dependent. This was in the early stages of UK ‘joose’. This was September 2016, and haze as a word was transforming from the meaning of light, misty appearance, to mean near-total opacity.

Earlier that year, Cloudwater’s DIPA v3 (very much pre-NEIPA, still in its lightly-hazy, day-glow marmalade-orange, in the style of Human Cannonball etc) had firmly established the timetable and carrier’s charter of The Hype Train for the enthusiastic UK consumer. All of these things (and so much more) had happened across the Atlantic first, but the frequency of our cultural exchange of beer recipes had mutated into an exchange of beer culture, and the infection here had taken hold.

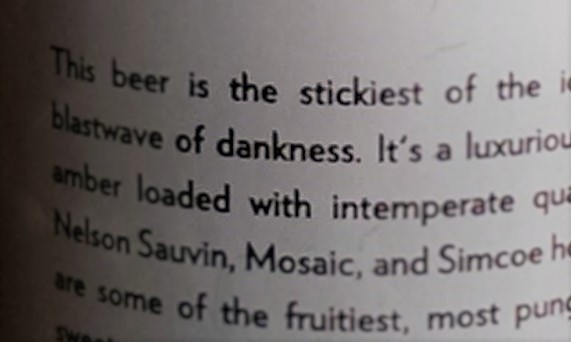

The urgency of releases (and their desirable appearance) had been democratically agreed upon by social media analytics and everyone’s wallets. As the releases piled up, the flavours and dry-hop charges intensified, attention spans shortened and a self-inflicted period of adolescence lengthened. The IBU Wars were over, and the insurgency against bitterness had begun. Technical capability and innovation research shifted to be focused almost entirely on how to increase flavour intensity in residually sweet beer (whether IPA, stout or kettle sour), and, in tandem, on how to mitigate the myriad technical problems resulting from trying to brew said sweet beers this way. Whatever we have gained, it feels like we’ve lost some things along the way.

Let’s go back a little, just before all of this took hold. Between 2014 and 2016, brewers in the UK were beginning to dabble in hazy IPAs. Some were more Vermont in influence (remember when that word Vermont was everywhere?), taking their cues from beers like Sip of Sunshine and Heady Topper, then New England ™ as a descriptor took hold, inspired by brewers like Treehouse, Tired Hands and Trillium. Some early trailblazers were blatantly plagiarised – albeit sincere and accurate – homages to these beers, others spliced a little of this exotic new DNA into their appearance and flavour.

This felt like a Golden Age to me, especially now, because the variety of beers available seemed to have no limit, and the variety within each style category was exciting in itself. IPA was opening up once again. Now we find ourselves chewing through trends (e.g. Brut IPA) at high speed, yet NEIPA (and pastrystouts and gloopjuice etc) don’t seem to be going anywhere, and are quickly being absorbed by the biggest brewers into their ersatz craft ranges, or at least the notion of them. These strange new creatures are undoubtedly styles of their own, but like Heisenberg (not that one, the physicist), the harder we try to observe them, the harder it is to measure them.

I’d like to think it is possible to return to that state of variety, quality and innovation (and I’m fully aware that there are breweries, bars and shops that encourage this view). The problem is that there is little incentive for many of those who can make that change more concrete.

Technical debate can obviously be boring, and beer styles and their definitions are, at best, unwieldy. At worst, they seem boorish and reductive. Still, I’ve found myself arguing the value of beer styles a number of times, not because I love them, but because without them, our understanding and interpretation of beers would be so much worse.

For example: a common criticism of BJCP styles is that any definition of any beer style can split a room, create a debate and detract from the sense of carefree fun inherent in beer. Personally, I think the best thing about styles is that that any definition of any beer style can split a room, create a debate and detract from the sense of carefree fun inherent in beer. We should relish debate and profit from it with understanding, tolerance and wisdom.

If these styles and their parameters are important, should they get in the way of beer evolving into new and exciting things? I respect the idea of Beer Everything®️ and pushing beer’s boundaries at a fundamental level. It’s a necessary component of the culture: challenge everything; be artistic in your exploration; be unpopular in your thinking; displease and reject the rule makers.

Even if the motivation wasn’t noble, and if it was purely attention-seeking and selfish, that approach would still have immense value in an industry abundant with the self-righteously certainty. Even if the intention is to sow discord and make a buck, disrupting the idea of normality in beer is inherently useful to anyone who has ever done something ‘a little bit different’ with a beer, as it broadens the spectrum of flavours.

If a beer already has quality, balance and value, all these additional pastry/fruit/fried chicken garnishes, in an attempt to satisfy consumers, ultimately dissatisfy them. If it’s what they really wanted, they’ll tolerate even further bizarre additions or twists. If it wasn’t bizarre or twisty enough, they’ll demand it should have had even further bizarre additions or twists. (Oh, and let’s not forget that there are a whole bunch of people who might be grossed out by the beer and never try anything like it ever again, tell their friends craft beer is stupid garbage, etc.)

Trends, however, show a problem. As those in the tastemaking vanguard of ‘what’s next’ in beer shuffle their playlists of familiar tunes even further away from drinkability in pursuit of Maximum Flavour (in many cases from flavourings), they get closer and closer to becoming alien and unknowable to everyone else. Those very styles and descriptions (and the arguments around them) that might turn people off initially are what they will cling to as they become more informed and experienced. That knowledge and debate helps inform our next set of explorations and excursion into the beer culture. Without them, you can become stuck in a rut. A very residually sweet rut.

The problem is that now our social media platforms of choice can seem equally unwieldy and reductive, and hardly suited as tools to open up discussion. Great examples of these newer styles (and there have been many, make no mistake) from the likes of Northern Monk, DEYA, Verdant, Cloudwater come and go at the same speed as the less competent examples, lost in the ever-shorter news cycle of new releases. I find myself in a job, once again, where the accomplished beers I have to celebrate need significantly greater noise to be noticed at all.

Does all this noise really have an effect? To some it seems like pure fluff, but the influence is undoubtable. Many of us have significant and unexpected power over the direction the industry takes, at multiple levels. Trendsetters, consumers, influencers, brewers and retailers each have a different measure of power. Consequences happen, regardless of intentions or irreverence towards their impact. In the words of George RR Martin’s spymaster Varys: power resides where men think it resides. As soon as we say, and believe, that consumers are driving what beers brewers have to make, it becomes true. For that bleeding edge of the market, it already has.

Brewers and beer professionals might try some of these highly-sought-after beers, even their own releases, and know that there are serious flaws and mistakes in them. But it doesn’t matter. The beers sell out on pre-order, retailers fill their tills, everyone demands more. This is much more than ‘the Emperor’s New Clothes’. This is millions of stark bollock naked Emperors thanking their tailors for such an excellent job with the diacetyl and hop burn.

To be absolutely clear: I don’t think that people who enjoy NEIPAs, pastrystouts, kettle sours (and combinations thereof) are stupid. Propagating this view is even more problematic than the FOMO culture around these beers. I enjoy these kinds of beers too, in moderation. Hell, I approach them with the same fascination as any style of beer that is difficult to make well. However, I do think everything from the language we use to the way these beers are produced, marketed and served has an individual effect, contributing to a systemic problem. That absence of the imperative, or at least wish to learn more, and try beers that might not be that great, or cool, in order to become more experienced, has been almost forced onto people by a monster of our collective making.

If you care for more than just intensity in beer, you should absolutely speak up about it, but not just by patronising or insulting those who enjoy beers you think are silly. This whole industry can feel incredibly silly at the best of times. If you think people should know more about what is or isn’t appropriate from a technical perspective; or that particular styles/breweries/pubs don’t get the attention they deserve; or how nobody remembers that one great beer from three weeks ago because it was replaced by fifty imitations – wonderful! Why not write a rambling blog post about it? (It made me feel a bit better anyway). Seriously though, any platform for opinion and discussion should be embraced. Disagree with someone else about any of this type of stuff? Be polite and ask about their reasoning. Have questions (or even strong concerns) about a particular beer – ask the brewery! Many of us in the industry welcome inquisitive questions and a thirst for knowledge with delight. It’s the sign of a healthy, open culture.

The situation we have now, however, is not one that inspires a lot of faith in the future; and that’s what the potential maturity of the craft sector must be measured in: faith. We need to decide where that faith will be placed: in each other’s collective experience and knowledge, or just the excuses we tell ourselves to justify our own feelings. Maturation must continue beyond the brewhouse, and it’s a collaboration in which we can all be involved.